Is your reproductive love story coming to an end? How to make the final cut.

Your crew of kids keep you busy and wondering where you’re going to find five minutes of uninterrupted time to spend with your partner, let alone a moment to yourself. Jumping from one activity to the next has left you and your partner breathless, and you often look at each other knowing the words that fill the silence: Remind me again why we did this? Sooner or later, most couples make a decision about closing the family unit, because who wants to keep using birth control when the problem can be solved permanently?

No turning back

Deciding if sterilization (vasectomy for men and tubal ligation for women) is the right choice for your family can be a painful and emotional journey because it is such a final act: it is permanent. The procedure can be reversed, but it is often painful and costly — upwards of $5,000 (out of your own pocket because reversals are not covered in most provinces) — and there aren’t as many practitioners offering reversals as there are doing them.

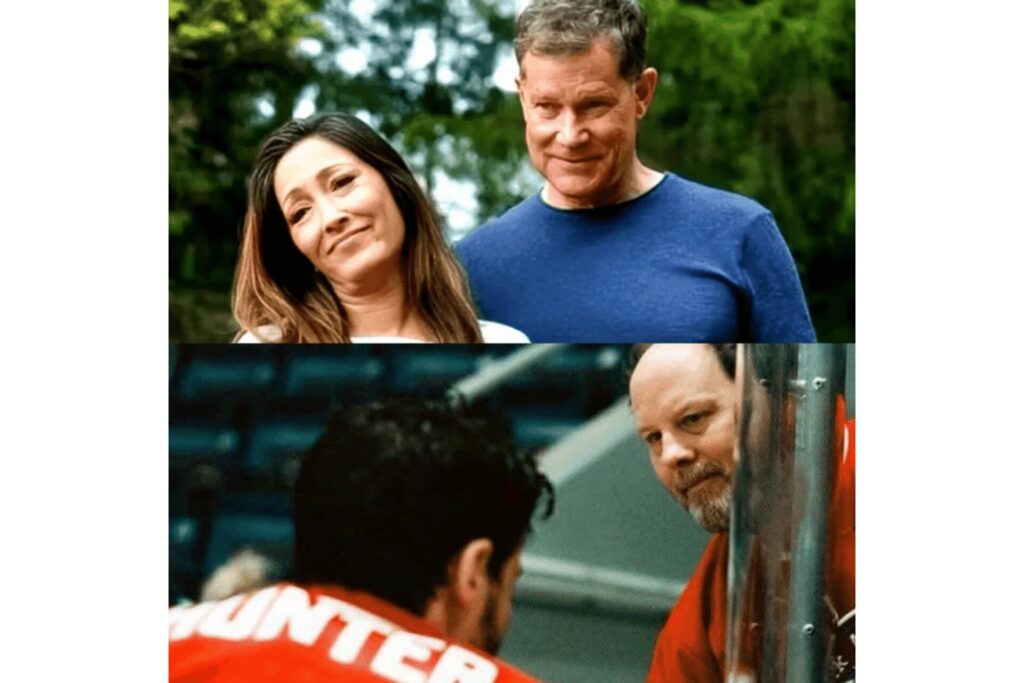

My husband and I, both 36, spent a year and a half debating this issue. He knew it was the right choice for us because we could not afford another child. I was approaching 35 and didn’t want to deal with the risks of a later-in-life pregnancy. Though these arguments made sense, I needed many months to deal with the reality that my husband and I would never have a child together. (We have children from previous relationships.)

After 18 months of deliberation, we agreed we had to close the conception gap; my husband had a vasectomy in January 2010. I rationalized it should be him to undergo the procedure because a) I had already suffered through childbirth, and b) I had an IUD in place for five years (and the removal of the IUD was painful and complicated). It was his turn to step up to the contraception plate.

The procedure was done in a vasectomy clinic about 40 minutes from home, took less than an hour, and required no sedation. He was offered (and took) an anti-anxiety pill. Provincial medicare covered the cost of the procedure, but we had to pay $150 for supplies (post-operative package) and services. After the surgery, he was uncomfortable; his movements were slower than normal, and he had to rest in bed for the remainder of the day. A week later, he was feeling more like himself, but it did take a good six weeks before all sensation and discomfort from the procedure were gone.

Is it for you and your partner?

For some couples, the decision to opt for sterilization is easy: when you know, you know. But even if you are confident, there are questions that should be asked. Tackling the difficult questions ensures emotional readiness for dealing with the aftermath of sterilization: no longer being able to have children.

Here’s a list of questions to discuss with your partner to help get you ready:

- Do you truly understand that this is permanent and, for the most part, irreversible?

- Will you regret not being able to have one more child? You need to be completely sure.

- What if one of your children died some time in the near future. How would you feel knowing you couldn’t have another child?

- What if you and your partner split — would not having children with a new partner be upsetting?

- Have other forms of contraception been considered (the Pill, an IUD, condoms)? Why do these forms of contraception not work for you as a couple?

- Is this a mutual decision? If it isn’t, neither one of you should feel pressured to do something you aren’t comfortable with. If such an impasse occurs, consider seeing a counsellor who can help you wade through the issues. It makes far more sense to spend $500 on therapy than it does $5,000 to reverse sterilization.

Though neither procedure requires spousal consent, it’s obviously not something to do without discussing with your partner first.

Male sterilization: the vasectomy

Vasectomies are performed twice as often as female sterilization and have a better than 99 percent success rate.

The procedure is done in either a hospital or clinic. If done in a clinic, no physician referral is required. First, visit your family doctor who will arrange for the procedure to be done in hospital. If you want to have a no-scalpel vasectomy, it’s best to seek out a private clinic that offers that option.

The two most common types of vasectomy procedures are no-scalpel and conventional (incisional vasectomy). In a conventional vasectomy, one or two incisions are made in the scrotum’s skin; the vas deferens (the tubes sperm travel through) are pulled out, cut, and tied (or clipped or stitched).

In the no-scalpel method, no incision is required, but rather the doctor punctures a tiny hole in the scrotum’s skin with a special instrument called a hemostat.This also stretches the opening so that the vas deferens can be reached. The tubes are then blocked, using the same method as in conventional vasectomy. Because no incision is made, not much bleeding occurs, and no stitches are needed to close the opening. It will heal quickly with little or no scarring. Scalpel vasectomies, though, are still the most commonly used technique.

The day before the surgery, the scrotum area has to be shaved (sorry, guys – this allows the doctor to see the area better). A local anaesthetic is administered to freeze the scrotum. The entire procedure takes less than an hour and you can go home right after (but have someone else drive). The two weeks following the procedure require rest and no heavy lifting. Scrotal support (a jock strap or very tight underwear) is strongly suggested, as is an ice pack between the legs (for 48 hours), which minimizes bruising. Common side effects are bruising and pain. Both eventually disappear.

Intercourse can resume two weeks later, but contraception has to be used because residual sperm remains in the duct and needs to be eliminated; it takes about 15 ejaculations before semen is free of sperm, so use protection, otherwise the whole thing may have been for nothing.

Female sterilization

A 2004 study on Canadian contraception use reported that eight percent of women in Canada opt for sterilization as a means of birth control. There are two types of procedures available. Tubal ligation — more commonly known as ‘getting your tubes tied’ — is a surgical procedure that cuts and seals the Fallopian tubes so that eggs travelling through the tubes won’t reach the uterus. The other is Essure, which involves insertion of spring-like coils into the Fallopian tubes (done vaginally).

For the most part, women don’t have any difficulty getting the go-ahead for sterilization, but in rare cases, women are denied by doctors. Not long ago, women were not considered suitable for sterilization unless they were over 40, had two children (one of each gender), and were married. In 2009, Tarrah Seymour, a 21-year old Toronto woman who was married with two kids, made national headlines when her obstetrician denied her the procedure — but this is the exception rather than the rule.

Tamara Bubyn of Moose Jaw, Sask., had just turned 40 at the time of her procedure. “The doctor asked and answered a lot of questions, and explained the different types available to me. Before I went in for my procedure he asked again if this was what I wanted. I waited a while for my procedure, but that was good because it gave me extra time to change or cement my thoughts.”

Tubal ligation

Tubal ligation is covered by most provincial medicare and should be considered permanent because, as with vasectomies, tubal reversals (tubal reanastomosis) are costly ($3,000 to $5,000), and are often not possible. Methods that avoid destroying a lot of tube have a higher reversal success rate. The failure rate for tubal ligations is extremely low — less than 0.1 percent.

Unlike vasectomies, clinics do not offer tubal ligations. It is surgery and has to be performed in a hospital because anaesthesia is used, and post-surgery complications can arise, such as infection and bleeding. A referral to a gynaecologist or obstetrician is required from your family doctor. Common post-surgery side effects are bloating of the abdomen, pain around the incision, nausea (from the anaesthetic), fatigue and cramping. It takes a good week before a woman will feel ready to get back to normal activities, and then only gradually.

Essure

Essure is a newer technique that does not require incisions or anaesthesia, making it a safer method than tubal ligation. The procedure is done in select hospitals across Canada and is covered by most provincial healthcare plans. The cost, if not covered, is $1,287. The recovery time is only one to two days and there are fewer post-surgery symptoms to deal with, namely no abdominal bloating, bruising, or pain (from incisions). Cramps and discharge can be expected from both. The one good thing about Essure is that it offers proof of effectiveness. After three months a woman has a test to confirm placement of the coils — peace of mind that doesn’t come with a tubal ligation.

Dr. John Thiel, Director of Women’s Health Clinic at Regina Qu’Appelle Health, sees Essure as becoming the standard of care for women seeking sterilization. “The actual procedure takes less than 10 minutes, the recovery time is much shorter than a tubal, and it’s not as risky because she doesn’t have to be put under. Most women are back to a normal routine later that day.” Alethea Spiridon is a freelance writer and editor in Durham Region, Ontario, and mother of three. She and her husband are very pleased with their decision.

Websites that have many resources for further information

For women:

The Essure procedure: essure.com

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada: www.sogc.org

For men:

The Gentle Vasectomy Clinic: gentlevasectomy.com

For both:

Sexual health: www.sexualityandu.ca

Originally published in March 2011.