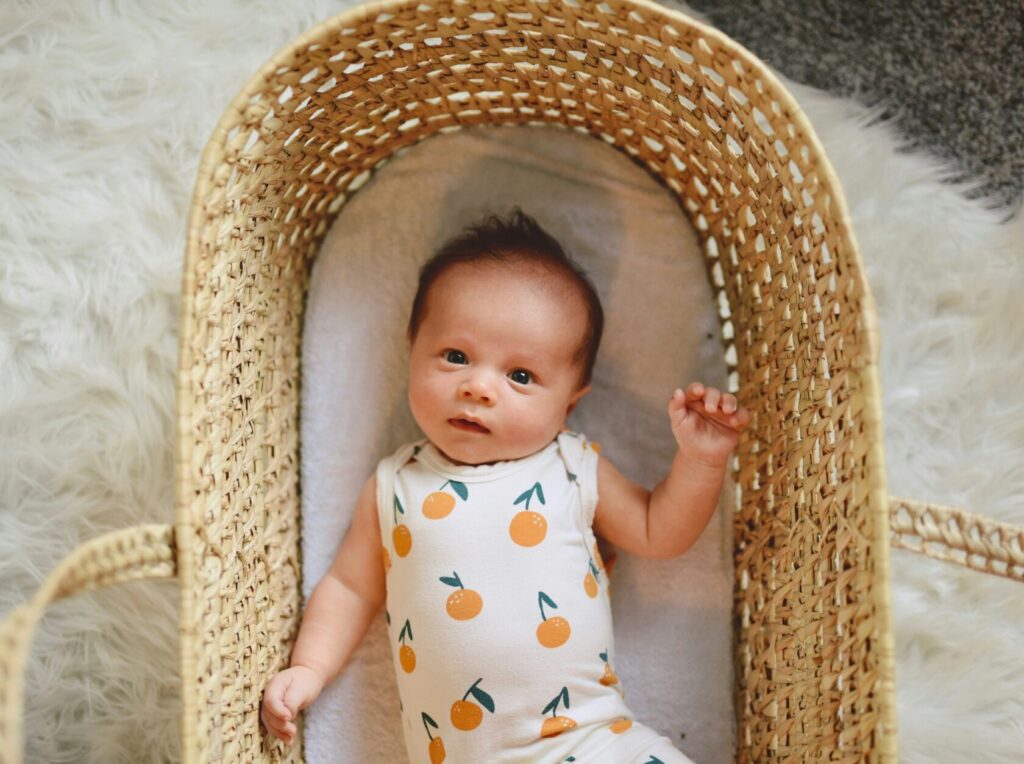

Pamela Roach’s son, Declan, was due on Christmas day. Because her daughter had been born late, Pamela expected she’d still be pregnant by New Year's Eve. So she was especially surprised when her water broke the morning of her 36-week checkup.

Though he was eight pounds and healthy, Declan stayed in the NICU, as was the hospital's policy for babies born before 36 weeks.

“At first we didn’t really understand why he had to be in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). But then we realized he was not quite ready to be outside,” Pamela said.

She had trouble feeding Declan, whose suck-swallow reflex was not yet developed. “He lost more than a pound that first night in the hospital,” Pamela said. “We were syringe feeding and trying to breastfeed and using bottles for those first few weeks until he got it figured out. He was also very sleepy, which didn’t help.”

Pamela had to pump to increase her milk supply and work hard to keep Declan awake while feeding. She and her husband also practised a lot of skin-to-skin care with Declan and nurses monitored his blood sugar and oxygen levels. Declan also had jaundice and stayed in the hospital for three days.

By his original due date, Christmas, Declan was back to his birth weight.

“We didn’t really realize. We just thought he came a little bit early. Now we realize that he is a little bit behind. At six months old, he behaves more like a five month old. But we just look at it like we got to have an extra month with him.”

Declan was what medical professionals call near-term or late preterm: babies born between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestation. Babies born between 37 and 38 weeks are considered early-term. These babies do not face the same difficulties as preemies but they are not full term.

More and more, doctors and researchers are finding that being just a little early can have its challenges, says Dr. Shoo Lee, pediatrician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. These can include:

- difficulty breastfeeding (may not latch well, can't coordinate suck and swallow, falling asleep)

- poor weight gain and dehydration

- breathing problems (trouble clearing fluid from lungs, more prone to apnea)

- getting chilled easily

- tiring quickly

- jaundice (two percent of term babies experience jaundice, compared to 18 percent of nearterm)

- more likely to develop infection

“These babies need to more rigorously be put on their backs. They have twice the risk of SIDS, as they do not have as much muscle strength,” Dr. Lee said. “They also don’t have as much body fat so are more prone to low blood sugar.”

Dr. Sheila McDonald, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Calgary, says issues can extend into early childhood. “These children appear healthy but there are subtle differences compared to their term counterparts. The research is showing there might be a risk for delays for cognitive and emotional development.”

In the early days it is important to recognize the risk of the baby not feeding well and to seek the support of a lactation consultant if you are breastfeeding. Pumping milk or tube or syringe feeding may be necessary. The baby’s blood sugar and oxygen levels must be monitored. Once mom and baby leave the hospital, a visit from a public health nurse might be needed and parents should be told what to watch for and what should prompt a trip to the doctor.

Dr. McDonald says there is also a slightly increased risk of postpartum anxiety in moms who have given birth to an early-term or near-term baby. She says proper nutrition and parent-child interaction with imitation games and reading, as well taking care of yourself and having social supports, will help set you both up for success.

“There may be a higher likelihood of challenges,” Dr. McDonald says. “But all of these risks can be mitigated by building a healthy foundation in the first few years of life.”

Near-term babies on the rise

Of the 380,000 babies born in Canada, 21,000 are near-term, says Dr. Lee. Noting early deliveries are becoming more common, due in large part to the rising age of mothers.

Older moms are more likely to need assisted reproduction. They are also more likely to have complications of pregnancy, such as diabetes or hypertension, which hamper their ability to carry a baby to term. Obesity also increases the likelihood of a pre-term birth.

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada advises not to schedule a Caesarean section before 39 weeks unless medically necessary. And Dr. Lee says most hospitals have policies stating that inductions or early C-sections for reasons such as doctor convenience or maternal demand should be avoided.

“Doctors and parents need to be aware that delivering early is not without its risks. It should be something we try to avoid if at all possible,” Dr. Lee says.

Originally published in ParentsCanada magazine, December 2014.