New from writer Erin Pepler comes Send Me Into the Woods Alone: Essays on Motherhood. This book touches on the major milestones of raising kids, from giving birth to lying to kids about the Tooth Fairy, as well as on the unattainable expectations placed on mothers today. Read on for one of the essays, “A Million Hands in One Vagina,” and just try not to laugh.

There is no easy way to tell a medical student that she’s stabbing you from inside your vagina. It’s a delicate subject, so to speak, and it’s particularly hard when the medical student is a young, nervous woman who is trying her best to see if you’re dilated while her supervisor, your borderline elderly male obstetrician, looks on. She’s trying. He’s waiting. You feel something sharp repeatedly jabbing your birth canal and hold your breath, trying to spare her the humiliation of knowing she’s hurt you. Is she wearing fake nails, or maybe a ring? If so, that’s a really prominent gemstone—not smooth like an opal but maybe a statement piece, modern and jagged. Whatever it is, you’re sure it’s breaking through her thin latex glove and will soon slice your insides. Oof. Checks like this are quick, you remind yourself, and it will be over soon. She pokes around, hesitantly asserts that you’re not dilated at all yet, and removes her gloved hand from your lady garden. Finally. You breathe deeply and relax.

Your doctor then throws on gloves and checks you again, of course, to see if the student was right. This time it doesn’t hurt—not that it’s pleasant to have an old man’s hand up in your box, but his fingers are free of jabby objects and his approach far more confident and efficient. In and out, yup, not dilated. Well done, intern. They thank you for consenting to the additional check. This is how doctors learn, of course! You smile and nod. No problem. Another prenatal appointment in the books.

Oh, vaginas. Many people won’t even say the correct name for that body part out loud, and then one day you find yourself in a dark ultrasound room, wondering how a fancy medical dildo is the only way to look for an early fetal heartbeat. That, my friends, is what I was thinking about when I was told there was a baby in me.

My due date changed several times, so near the end of my first pregnancy, around the time of the aforementioned appointment with the intern, it all felt like a guessing game. I knew I’d been pregnant for approximately nine months, so I assumed an infant was going to make an appearance soon. I was tired of constantly throwing up and feeling like garbage, and looked forward to being able to tie my own shoes again without Herculean effort. My breathing was laboured from walking and my hips ached from sciatica and a pinched nerve. I limped when I moved, my limbs were swollen, and, no matter how exhausted I was, I couldn’t sleep unless I was propped up with an elaborate arrangement of pillows to thwart my acid reflux and keep the hip pain from flaring up. When I did fall asleep, I’d wake up to pee fifty times, carefully rearranging my pillow pile after every trip to the washroom. When morning came, the vomiting would start again. People spoke of labour as being a real ordeal, but I figured it couldn’t be half as bad as my pregnancy. Or maybe it would be, but at least then the pregnancy would be over. Either way, I was ready to get the show on the road.

And so, when labour finally started, I was thrilled. Get this baby out of me, I thought. Just please don’t let me poop, tear, or require an episiotomy.

It may seem strange that these were the things I feared the most about labour, but they’re reasonable concerns. Someone had casually mentioned to me that my OB reportedly “loved” episiotomies, and countless friends had shared stories of tearing, which didn’t sound any better. Very few admitted to pooping while pushing, but according to every pregnancy book, it was totally plausible. As a woman who has never passed gas in front of her husband, I found this possibility particularly horrifying. “If it happens, it happens,” my husband said, shrugging. He’s been free with his bodily functions from the early days of dating, whereas I’ve held in a single fart for a three-hour car ride and cannot even say the word aloud. I shook my head emphatically. “I’d die if I pooped in labour. I would just divorce you right then and there, so we’d never have to acknowledge it again.”

It was with this mindset that I instructed my husband to remain near my shoulders during the birth. “I want you to have the same view I’m going to have,” I explained. “Like a movie birth—where I’m pushing and you stand there and encourage me, and then the baby emerges from under the sheets, in the doctor’s hands. There’s no reason for you to see my birthing vagina. It’s not the same as a sex vagina. I’d like to have sex again, eventually, and for us both not to have a visual reference of the train wreck of the birthing vagina. Please.”

My husband was amused, but he agreed.

I wasn’t afraid of giving birth, but I still didn’t want my husband to see it happen up close, nor did I want to witness the gore myself. I could breathe through contractions, bear down, and push like a champion, but I didn’t want to see the baby crowning or be distracted by the reflection of my anus in a birthing mirror. I was certain my body would come through and get the baby out safely, but I was far more comfortable feeling things happen than seeing them dead-on. A year or two before my first child was born, I’d had my gallbladder removed. The idea of surgery hadn’t stressed me out, but if you’d asked me to stay conscious and watch the procedure in a mirror, I would have firmly declined. Sure, a baby is not a gallbladder, but I feel like the same theory applied. I didn’t need to see things from the same angle as my obstetrician. I like to feel in control of my body, and I also like to deliberately avoid things that freak me out. Is that too much to ask?

When I noticed mild, steady contractions one Wednesday morning, I hopped on the subway and went to my weekly OB appointment, conveniently scheduled for that same day. My OB checked me, noted that I was a centimetre dilated, and agreed that I was in the early stages of labour. “So I’m going to have the baby today?” I asked excitedly. “Probably tomorrow,” he replied, with the gentle expertise of a man who has seen several thousand cervixes. He explained that I was progressing slowly and should rest at home for as long as I could. He also suggested that I eat and take a nap while I was still comfortable, so I’d have energy later on. I called my husband, bought a bagel, a chicken noodle soup, and an iced cappuccino from the Tim Hortons in the hospital lobby, and decided I could justify a cab ride home. I was in labour, after all.

The next morning, the contractions were frequent and much stronger but still bearable. I was in significant pain, but not agony. “Do we go to the hospital?” my husband asked. I didn’t know. The contractions were getting closer together and lasted longer, but I’d expected worse. Still, it seemed reasonable to check in on things. We went to the hospital, optimistic that we’d be told labour was moving along well.

I was greeted by nurses and led to a small room where they would check my dilation. Memories of the ringed intern flashed through my mind, and a young doctor I’d never seen before snapped on his glove and reached for my cervix. A gush of liquid flowed onto the hospital bed, and we locked eyes. “It’s not pee,” I said meekly. He nodded in awkward agreement: “Your water just broke. You’re only about a centimetre dilated though. Maybe two. You can go home for now and come back in twelve hours or when your contractions are less than five minutes apart.”

Come back in twelve hours? Sure, I’ve already been in labour for a full business day, but whatever. Dilation was not a race I was winning, and I wanted another iced cappuccino. (Truly, I cannot understate how many cold, blended drinks I consumed while pregnant. One of the few things that would temporarily stave off my nausea, they were my lifeblood.)

My contractions were already around five minutes apart, but I heard “two centimetres” and went home, certain I’d be pregnant forever. I was incredibly wrong. Within the hour, I was doubled over, gasping in pain, cursing the doctor and my husband and everyone I’d ever known. Lying down hurt and bouncing on the yoga ball was hell, so I tried the shower. When the water hit my back, I felt moderately better. More importantly, I felt calm.

This is how I found myself labouring alone in the shower for several hours, pained but content. My husband checked on me often and timed my contractions as they got closer together. Twelve hours after my water broke—over twenty-four hours since my OB appointment and the approximate start of my labour—I agreed to go back to the hospital. We called a cab.

I had not anticipated how awful it would feel going from standing in my hot shower to sitting in the back seat of a cold, bumpy taxi. The hospital was only ten minutes away without traffic, but snow had started to fall and, as luck would have it, it was rush hour. The pain seemed to double in a matter of minutes, and I soon found myself quietly whimpering in agony, writhing like an injured animal as we crawled along. My husband put on a brave face and assured me we’d be there soon. The cab driver, however, was not as confident.

He quickly tapped a series of numbers into his cellphone and began speaking Arabic in a low, concerned voice. The words “pregnant” and “baby” leapt out at me in English, and as the call became more animated, I realized that he thought I was going to give birth in the cab. He looked back at me in the rear-view mirror, his voice raising in both volume and pitch as he spoke into the phone. “I’m fine!” I squeaked out, my fists clenched in pain. My torso felt like it was being ripped apart by sharks, but I felt no urge to push and was sure we’d make it to the hospital. “Don’t worry, these things take a while.” He drove fast and aggressively, even for a cab driver, and eventually screeched to a halt in front of Mount Sinai Hospital, where I myself had been born. I have never seen relief like the look on that cabbie’s face when I stepped out of his car, still pregnant, having not given birth in his vehicle. We tipped him well, as one does when they scar a person for life. (I’m sorry, cab driver.)

Another doctor, another hand in my vagina, and then the proclamation that I was—get this—two centimetres dilated. “But…I was two centimetres over twelve hours ago,” I protested, barely able to speak through the pain. “My water broke this morning and I’m dying. Like, it doesn’t stop, it’s just pain and then worse pain.” Sympathetic but busy and not entirely convinced I was accurately describing my pain, the medical staff asked if I wanted an epidural. I nodded, abandoning the idea of a non-medicated birth. Whatever drugs they had, I wanted—all of them, as quickly as possible, straight into my veins. Plans change and choice is good.

While epidurals aren’t for everyone, I will tell you this: they are for me. After a few misses with the needle and a brief period wherein only one side of my body was numb, the pain all but disappeared. Soon after, I was lying comfortably under a blanket, listening to my iPod and praising modern medicine. The music was great for relaxing and letting my body rest, and also for drowning out the sounds coming from the next room. My hospital neighbour, a stronger woman than I who had chosen not to take the epidural when offered, let out a steady stream of long, guttural moans. It sounded like a bear had been shot and left to die slowly in the woods—or two inebriated gorillas attempting to make love in the echoing mountains. The sound vibrated through the thin hospital walls and continued for hours, worsening as the night went on. I turned up the volume in my headphones and hoped her baby would come soon.

Being numb from the ribs down was pleasant, and also made the parade of hands inside my vagina over the next few hours easier to tolerate. Oh hey, person I’ve never seen before but who is apparently the doctor in charge right now, you want to check my cervix? Go for it, let me know what’s up. Student doctor who needs to cop a feel so she can learn? Sure, get in there. The hours went on and my labour seemed to be frozen in time—more checks, very little progress. Shifts changed and new hands explored my nether region, always with the same news: not much dilation was happening. They hooked me up to an IV of Pitocin and promised things would speed up.

Fortunately, they were right. When I finally hit full dilation approximately fifty hours into my labour, the doctor had an epiphany. “Oh!” she said. “This baby is posterior. She’s face up and has been stuck behind your pelvic bone—that explains why you weren’t dilating.” It also meant she might continue to be stuck there as I pushed, which resulted in a quick debriefing on forceps, vacuums, and other possible interventions.

“I don’t want an episiotomy!” I insisted. The doctor promised she’d do her best to avoid one, quietly noting that a C-section was probably a bigger concern. Tables and medical carts were set up, nurses sprang into action, and the doctor reached back up inside me to check the baby’s position. By now, I barely noticed when someone was wrist-deep in my lady bits—it would have been weirder had someone not been in there, honestly. This time I got good news.

The doctor locked eyes with me with the intensity of a high school football coach on game day. “This is not a big baby. Listen to me—you’re going to be fine.” I nodded, and then pushed with all my might.

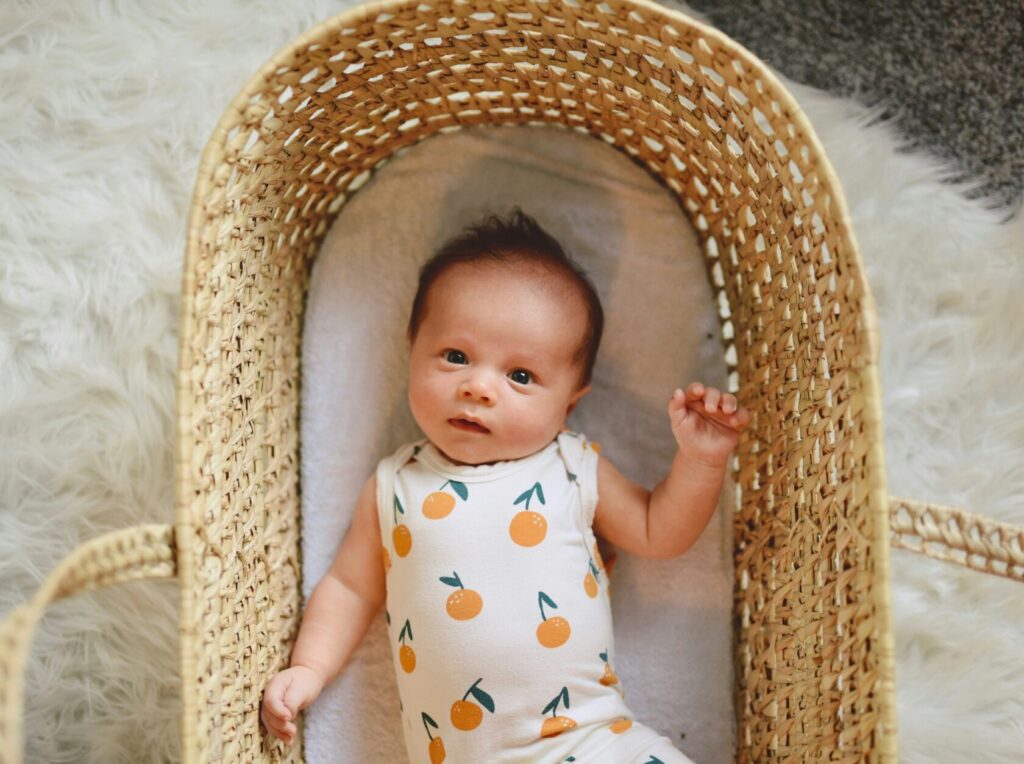

Less than ten minutes later, I was a mom. Weighing in at just over five pounds, my tiny daughter was immediately my favourite person on the planet. I barely noticed as the doctor threw me a handful of stitches before giving us some alone time as a family of three.

What’s interesting about childbirth is that, unlike pregnancy, we’re allowed to acknowledge how gross it is. Complain about your pregnancy? Shame on you, lady. Mention that you had a rough labour and delivery? Watch the sympathy roll in. Everyone knows that giving birth is the worst and anyone who’s done it is a superhero. Yes, delivering a baby is a wonderful miracle of the human body, but it’s also super painful, occasionally disgusting, and marks the beginning of a postpartum aftermath no one truly prepares you for. Have you ever seen an umbilical cord in real life? It looks like a gigantic, pulsating tapeworm that’s attacking your newborn. It’s messed up, and then they ask your husband to cut it with scissors, which is even wilder. They actually cheered my husband on like he was about to christen a boat, and then praised him for cutting the thing successfully. A woman spends over nine months gestating a child and then labours to birth it, guided through the process by a dedicated medical professional. At what point did someone suggest the father be given some sort of ceremonial role involving blood and scissors? Do men really need to feel important at every event? Maybe just sit back and let women have this one thing.

There is no denying how incredible it is that our bodies create and grow humans, and later release them from whence they came. I cannot whistle and sometimes say, “Righty tighty, lefty loosey,” in my head when opening a jar, but somehow I’ve managed to push two small humans out of my vagina without completely destroying my body. Nature is amazing and so is medical science, and even so, childbirth is still a total shot in the dark. After all of this, my second labour was textbook—a slow build of contractions, steady dilation, a quick transition, and some pushing. A walk in the park, relatively speaking. I’ve said I could give birth to my son every weekend if I had to, and I mean it—the experience was so calm and easily manageable, it almost felt like cheating. Maybe birth isn’t always the worst, I learned. (My son himself is not a reflection of his birth story—he may have ridden in on a gentle wave but he’s a hurricane of a boy who has never, ever been described as “easily manageable.”)

But back to my box, and the million hands I got to know so intimately. The day my daughter was born, there were exponentially more unique pairs of hands in my vagina than I’ve had sexual partners in my entire life. Manicured hands, wrinkled hands, young intern hands, hands I don’t even remember. Hands that knew what they were doing and hands that used my body as a learning tool. A million hands in my one vagina. It was fine, because I consented to it and felt respected throughout the process. At no point did I feel uncomfortable or regret choices that were made. That’s not everyone’s experience, but it was mine—though on some level, I feel like maybe I should have at least tried to remember their faces.

Cover photo courtesy of Invisible Publishing. Excerpted with permission from Send Me into the Woods Alone: Essays on Motherhood by Erin Pepler (Invisible Publishing). $21, chapters.indigo.ca