It’s early winter and I’m a volunteer at the

It’s early winter and I’m a volunteer at the

local elementary school. I have high hopes

of becoming a school teacher and want to

gain some hands-on experience. Inside the

classroom, 28 little children sit in their chairs,

working on their ‘paper cutting skills.’

I glance up from supervising a child when

a most wondrous sight catches my eye: snow

flakes are softly falling outside the window.

Great, fluffy flakes float gently down from

a purple sky. It brings to mind a cherished

snow globe I had as a child. It was a famous

landmark – the Eiffel Tower I think – encased

in a plastic dome. When I shook it, the little

white flakes would descend in a swirling

mass, to land at the bottom. Then I’d do it all

over again. The toy would amaze and amuse

me for hours on end.

It’s a magical world, but the teacher has

a different opinion. She hurries over to the

window where the children are already

gathered to watch the snow fall. Swiftly,

abruptly, she draws the curtains closed.

“The children are getting distracted,” she says.

The suspicions I had been harbouring

about the nature of schooling and how

it might actually prevent learning are

being confirmed in this very classroom.

These curious minds are missing out on

experiencing falling snow. They don’t get to

observe, engage, or be awed by it. Judging by

the looks on their faces, they know they are

being cheated but can’t do anything about it.

Instead, under the teacher’s management,

they must return to their seats and complete

the assignment before the bell rings. At that

point, they will move to the next learning

opportunity that’s been prescribed for them.

My hand hovers uncertainly over my

pregnant belly. Is this what awaits her?

Curriculum, shmurriculum

Fast forward a few years and my daughter is

four years old. She’s eager for the world and

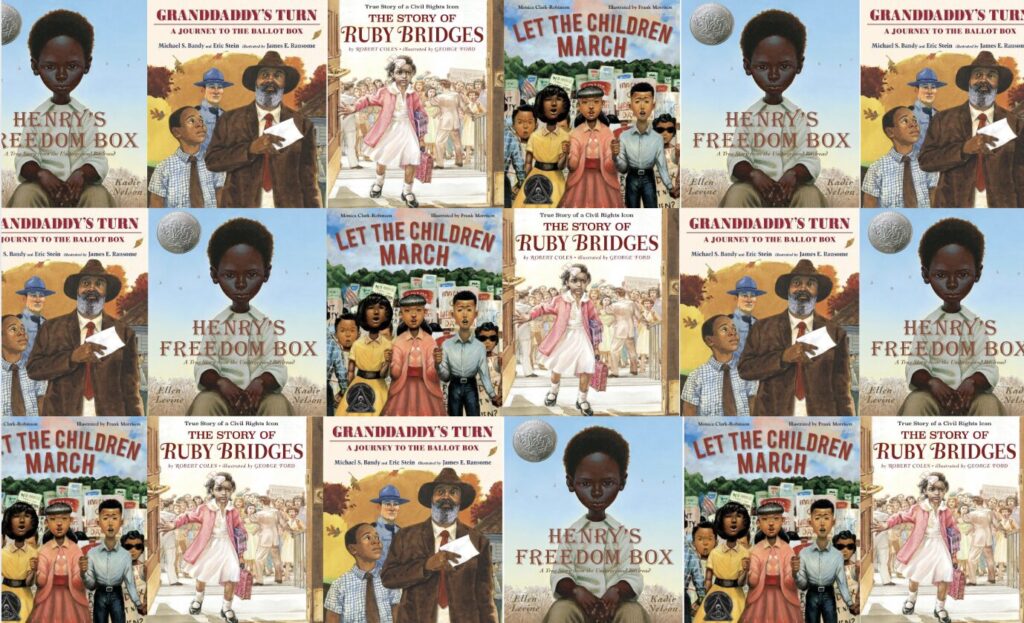

she wants it all – right now. She’s memorizing

entire books by the wagon-load;

she’s singing at the top of her

lungs. She’s playing “We Shall

Overcome” on the recorder.

She’s role-playing her favourite

characters – Pooh Bear, the

Paper Bag Princess, Thomas

the Tank Engine. Her two

younger sisters, ages one and

two, are bright-eyed and in a

wild frenzy to catch up with

her. They want to dance like she

does. They mean to climb trees

and build forts, dig up worms,

bake cookies, paint pictures

and ride a tricycle like her.

Two years later, my eldest

daughter is six. She’s making

intricate models with origami.

She’s demanding to see the

universe through a telescope.

She’s outraged that there was

a time when women weren’t

permitted to vote. She’s

passionately playing the role

of Frodo Baggins in the Lord of the Rings – the

book that will shape her sense of fellowship,

fairness and even love, for years to come. Her

sisters aren’t far behind – one is figuring out

how to read, the other never walks by the

piano without sitting down and playing a

piece.

And the feeling I’m getting is a dizzying

fascination and wonderment as they set

the pace. It’s their interests, their passions

that take the lead and drive the learning. I

am amazed by the way they uncover new

meaning or add unexpected dimensions and

surprising twists and turns to projects they’ve

been working on for weeks. I can’t imagine

missing all this. My husband and I make do

with his income so that I can be home for the

short time that we have them.

A few more years pass, and my children

are still not at school. I’m still not a teacher.

But I’m every bit as interested in education.

I’m figuring out how this works. It’s not

about imposing my ideas on them; it’s about

exposing them to as much of the big, wide

world as they can take. It’s about facilitating

opportunities for them to grow in all ways.

Still, it’s tricky. Surely I have to teach them

since they’re homeschooled. I go and buy

curriculum. I check out other people’s kids

and what they know and compare my kids. I

worry whether they’re measuring up.

All the time, the proof is staring me in the

eye. Before me are confident, questioning

children; their sense of adventure and

curiosity remains intact. I do my best not to

hamper it. I chuck the

curriculum. From now

on, I have to teach myself

the art of respectful

listening and observation

of patience and timing.

Especially timing. My

oldest, despite being

literary, didn’t really read

until age eight. “Mom,”

she says. “I’ll read when

I’m ready.” I have to trust

her. I know that were

she in school, her lack of

reading would be cause

for concern. (As it turns

out, by the time she was

12 she had already been

published. At 15, she had

written two books and

published even more

poetry).

As I navigate the waters

of ‘well roundedness’ and

‘socialization,’ I steer clear

of ‘what they should know,’ and ‘what will

the neighbours think?’ I soak up the wisdom

of those who have ploughed the depths of

alternative education – Ivan Illich, John Holt,

Grace Llewellyn, Wendy Priesnitz – and I am

reassured that I am doing okay in this new

territory called Unschooling, a term coined

by John Holt in the ’70s to describe interestbased,

personalized learning.

I read John Taylor Gatto and I am set at

ease, once and for all. Probably the best

known advocate of unschooling today, Gatto

claims that “genius is as cheap as dirt,”

because it really is. Once you start to value

dirt, let go and let grow. He refers to it as

‘open-source learning’; learning is available

everywhere in life and not restricted to

‘places of learning’ – namely schools. Gatto

proclaims with the assurance of a person who

has worked with young people for most of his

adult life, “Nobody can give you an education.

You have to take an education.” And we’re

taking it: the library, the neighbours, the

Internet, the university, museums, the

bookstore, interest groups, grandma and

grandpa.

I joined unschooling groups, both local

and online, for a little support. The children,

with their ferocious appetite for life, need

more; more friends, more community, more

opportunities. We started a radio show called

Radio Free School, created by, for and about

home learners. The show ran for six years

out of the university campus. We interviewed

people from all walks of life doing all kinds

of interesting work – a physicist, a farmer,

a novelist, a belly dancer, an archaeologist

researching DNA who let us hold a twomillion-

year-old piece of poo from an ancient

cave in China.

We spoke with researchers on alternative

education and advocates for natural learning.

We gained confidence as we met adults who

were unschooled and who reassured us that

unschooling works.

From unschool to school

Six years later, my older daughters are 13 and

11. “What’s school all about?” they wondered.

“Can we go and see?” They did and they

stayed, leaving just one child at home. It’s

different with one. It’s lonely and somehow

more challenging without having another

child to bounce off. Unschooling changed as

we adapted to the new set-up.

Today, my oldest daughters are in

public school entering Grades 10 and 12.

My youngest has never set foot in a school

building but this fall, she will be joining the

Grade 9 ranks to explore what this school

thing is all about. She assures me she is

happy as an unschooler, but would like to

attend for a semester before returning to

unschooling. She’s a physical type and needs

plenty of exercise. Her ambition is to play

soccer for Canada as well as to work with

dogs. She’s working hard at learning French

because family friends who live in Belgium

have invited her to visit. She likes structure so

we’ve drawn up a daily schedule that includes

maths, poetry, art and Canadian geography.

The learning happens as a result of the

goals, not the other way around. And this

philosophy is still with my other daughters.

Once unschooled, always unschooled.

They call me a radical and I laugh because

I am about as radical as butter. On reflection,

what I’ve tried to do over the years, in the

belief that humans are natural born learners,

is to safeguard those characteristics which

are catalysts to learning and living: curiosity,

a sense of wonder, humour, creativity, the

welcoming of challenge and surprise.

That to me is not radical. Seen from this

perspective, what is radical is school as we

know it: compulsory curriculum dictated, 9

to 3, five days a week, 10 months a year, for

12 years. It’s only been that way for about 150

years, which on the scale of human history,

is pretty recent. Me thinks this could be the

‘great experiment!’

Freelance writer Beatrice Ekwa Ekoko lives in Hamilton,

Ont., with her husband and their three daughters. Her

book, Self-Directed Learning: What it is, how to do it, and

those who have done it, is due to be published this fall.

Radiofreeschool.blogspot.ca is still going strong.

Originally published in ParentsCanada magazine, August/September 2012.

Scrambled Egg Tacos

Scrambled Egg Tacos